Mastering the Business Model Canvas: A Deep Dive Guide

After founding two startups, I’ve come to a conclusion: the Business Model Canvas (BMC) is the single best tool for sparking commercial thinking in new entrepreneurs.

I first encountered the Business Model Canvas in a college business class. Back then, I learned it alongside other renowned strategic tools like Porter's Five Forces, SWOT, and PEST analysis.

However, when I actually started my own business, I had a distinct realization: many of those traditional tools were too grand, too abstract, and often devolved into “correct but useless” theoretical fluff.

The Business Model Canvas is a classic for a reason. Not only does it help entrepreneurs clarify their thinking at a strategic level, but more importantly, it acts as a bridge between strategy and execution. It forces you to drill down one layer deeper, translating high-level strategy into tangible paths and methods.

Frameworks Beat Brute Force

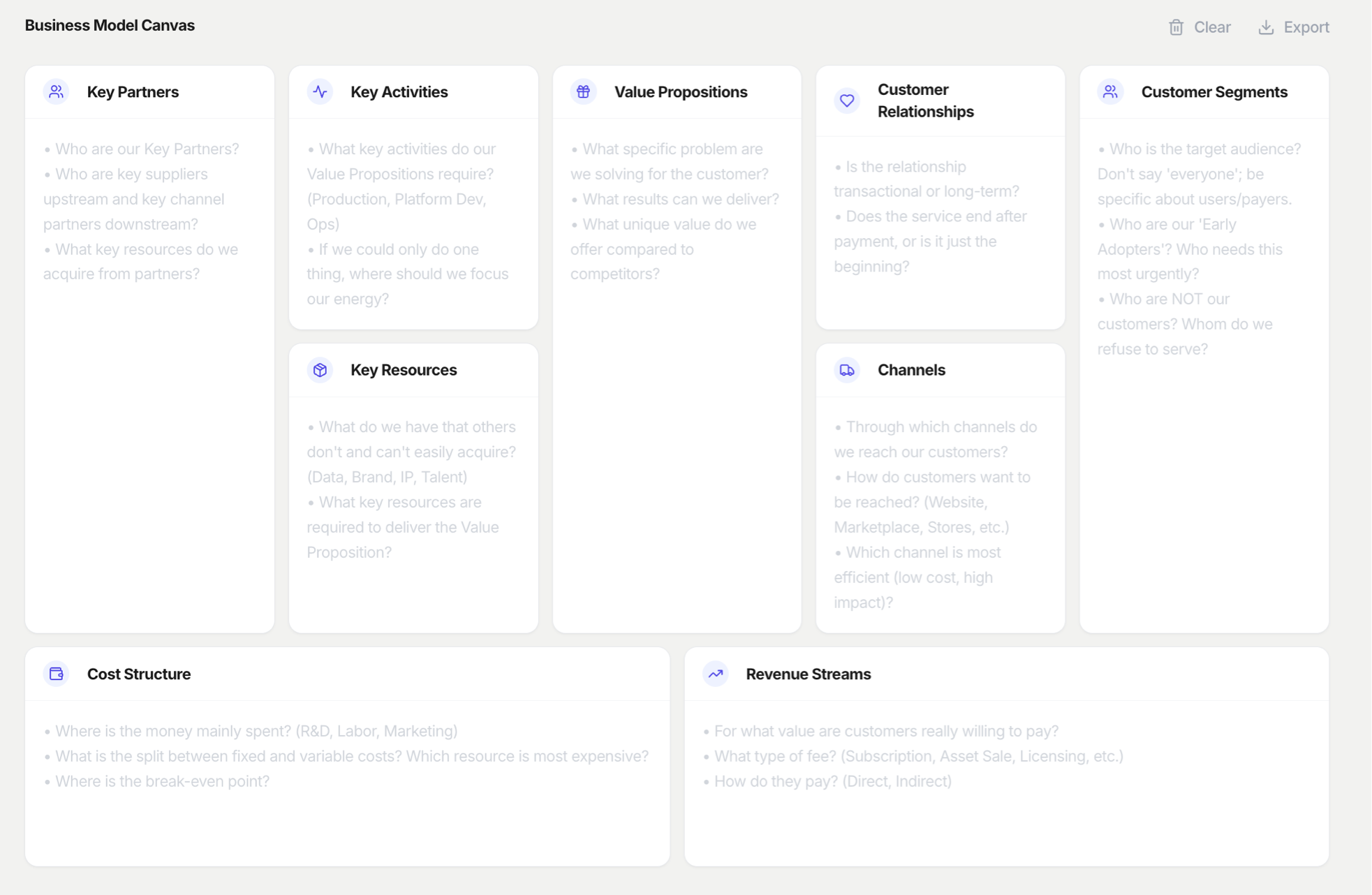

The Business Model Canvas was proposed in 2005 by Alexander Osterwalder, co-founder of the consulting firm Strategyzer. It consists of 9 blocks, posing 9 essential questions that every enterprise must answer when designing its business model.

These 9 questions are independent yet interconnected, often pulling in different directions, requiring entrepreneurs to constantly weigh trade-offs.

For a startup, having a framework is more important than just “winging it.” We’ve all experienced that moment: you’re pumped about an idea, but when it comes to turning it into a real company, you don’t know where to start. The BMC turns chaotic thoughts into actionable directions. Its true value lies in the mental clarity you gain while answering these nine questions.

Filling Out the Canvas: A Deep Dive

If you just fill in the boxes literally, you’ll likely end up with a mediocre business model. To create something profound, we need to deconstruct the 9 blocks and understand the essential question behind each one.

Here is my breakdown, incorporating lessons from my own journey.

1. Customer Segments

The starting point of every business can be summarized in one sentence: Whose problem are you solving, and what is that problem?

No company can solve all problems for all people. Therefore, the first question is: Who is your target customer?

This seems easy, but many stumble into two major traps right at the start:

Trap #1: The target customer is "Everyone."

Everyone wants to serve more customers because volume equals profit and potential. But the objective law of business is that even for the same need, solutions differ across demographics. Take clothing brands:

- Uniqlo: Targets the mass market seeking comfort.

- Lululemon: Targets urban, pioneer women seeking the beauty of body contours.

- Arc'teryx: Targets "light luxury" white-collar workers bringing outdoor style to city life.

You see, everyone wears clothes, but based on the scenario, the market splits into many categories. If your clothing brand’s segment is "everyone who wears clothes," or your cat food brand is "everyone who owns a cat," you will find that this broad boundary ensures you catch no one.

You must granularize. Drill down to specific people, specific scenarios, and specific needs. Defining "who we don't serve" requires courage, but it focuses your limited resources on your true customers.

Trap #2: Confusing the "Buyer" with the "User."

This sounds like a rookie mistake—how could you mistake your customer? But it’s incredibly common. In many products, the person paying the bill is not the person using the product.

In these cases, we often call the actual user the "User" and the payer the "Customer."

Take the enterprise SaaS platform Lark (Feishu) as an example. It’s a sophisticated collaboration tool loved by users for its documents and tables.

Lark is loved by employees, but is the target customer the employee who uses it daily? No. The customer is the Business Owner. The needs of the customer and the user often conflict. Employees might want a tool that allows them to coast; the Business Owner wants a tool that drives efficiency and output. The owner pays for Lark as a "management tool." The Business Owner is the real customer; the employee is the user, and in this dynamic, they are the "managed."

Similarly, for baby formula, the user is the infant, but the customer is the parent. Therefore, the selling point must address the parent's anxiety about health.

Key Takeaway: Distinguish clearly between the User and the Buyer, and nail the core demands of each.

2. Value Propositions

Your Value Proposition is not just your product; it is the philosophy with which you solve the customer's problem.

Does your product save time, improve efficiency, provide psychological satisfaction, or solve a utility issue?

You must view Value Propositions from two angles:

- Transactional View: What specific problem are we solving?

- Competitive View: What unique value do we offer that competitors cannot?

Tesla’s value proposition is high-performance electric mobility, targeting affluent, tech-forward consumers. Its unique value—separating it from competitors—lies in its world-class autonomous driving tech and supply chain integration.

Key Partners

Key Activities

Key Resources

Value Propositions

Customer Relationships

Channels

Customer Segments

Cost Structure

Revenue Streams

Furthermore, a strong value proposition serves as a product compass. Because Tesla stands for "Performance and High Tech," building the Cybertruck or the Optimus robot makes sense—they align with the core philosophy.

This applies to small businesses, too. Look at tea and beverage chains. Chagee pitches "Oriental tea going global," focusing on culture. Mixue pitches "High quality at a low price," focusing on affordability. Heytea pitches "Inspiration," focusing on original design and aesthetics. Same industry, completely different product forms defined by different value propositions.

3. Channels

Simply put: How do we reach the customer?

Building a product isn't enough; you have to put it in front of the customer.

- Owned Channels (Direct): High margin, but slow to build and high cost.

- Partner Channels (Retail/Distributors): Fast scaling, but you hand over margin to the channel, and rapid volume can break your supply chain.

This is a game of trade-offs. Which channel offers the lowest cost and best effect for your current stage?

4. Customer Relationships

This answers the question of Customer Lifetime Value (LTV). Is it a one-off transaction (Real Estate)? Or continuous (Barber/SaaS)? Is payment the end of the service (Supermarket), or just the beginning (Consulting)?

Consider two factors:

- Unit Price vs. Frequency: Low price/High frequency business (Snacks) needs a membership system to lock in habit. High price/Low frequency (Real Estate) requires building relationships before the need arises. High price/High frequency is the holy grail (requires consultative service). Low price/Low frequency? I suggest you find a different business.

- CAC vs. LTV: In the internet age, Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) is high. If acquiring a user costs $30, and they spend $5, you lose money. You need retention strategies to make them spend 10 times so the LTV covers the CAC.

5. Revenue Streams

This block answers three questions:

- What value is the customer really paying for?

- What are they paying? (Subscription, fee, purchase, rent?)

- How are they paying?

Let's look at point #1. A gym-goer buys dumbbells not for the iron, but for the fitness goal. Parents don't pay for "classes"; they pay for the hope of their child's future. A restaurant owner buys map optimization services not for a pin on a map, but for foot traffic.

Deconstructing the "value paid for" solidifies your business foundation. It helps you verify if your revenue structure is stable.

6. Key Resources

This is your "Ace in the Hole." Market need (Segments/Value Prop) is about what the market wants. Key Resources is about what you have.

What do you have that is rare, hard to copy, and crucial? (Data, Brand, Patents, Exclusive Licenses).

- Tesla: AI & Battery Tech.

- Xiaomi: Supply Chain Efficiency.

- Disney: IP Rights.

Two Common Misconceptions:

- Overestimating "Talent": Yes, talent matters. But objectively speaking, for most companies, staff are not a "Key Resource" in the strategic sense. A key resource is something the company cannot function without. For an oil company, despite having brilliant engineers, the Key Resource is the Oil Field, not the talent.

- Listing things money can easily buy: I once knew a founder who insisted his fancy office in the World Trade Center was a Key Resource because it signaled power. It wasn't. Any competitor with cash could rent the office next door. If it can be bought, it's not a barrier.

7. Key Activities

What are the few things you must do—and do often—to keep the model running?

- For a manufacturing factory, the key activity is Production.

- For a brand company like Nike or Pop Mart, the key activities are Marketing and Design.

The "Key Activities" block helps you focus and find your center of execution. If you are struggling to define this, I have a good heuristic: If the CEO could only do one thing, what should they spend their energy on?

8. Key Partnerships

Partners fall into two dimensions:

- "Cannot do without": The entire chain depends on them. Even a giant like Apple needs Foxconn. Without manufacturing partners, Apple's great ideas and designs would never land.

- "Better with": Outsourcing non-core tasks to move faster. E-commerce companies outsource logistics; construction firms outsource finishing work. The logic is simple: If we aren't good at it, or it's too expensive to do in-house, we outsource it to share risk and accelerate growth.

9. Cost Structure

Looking Now:

- Where is the money going? (R&D, Labor, Traffic?)

- Is it Fixed or Variable? What is the most expensive item?

Looking Forward:

- Where is the Break-even Point? How many units must we sell to cover costs?

Cost is the "drag" on development. It keeps you rational and awake. Analyzing structure also validates your model type:

- Cost-Driven (e.g., Food Delivery/Walmart): "Saving every penny counts." The focus is on Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) and extreme efficiency.

- Value-Driven (e.g., Hermes): Costs matter less; experience matters more. The focus is on brand premium.

- Software/Internet Companies: High fixed costs (R&D), low variable costs (replication). The goal is to scale rapidly to pursue high gross margins.

Business Models Must "Flow"

Many people confuse Business Model (how you operate) with Strategy (how you compete and change).

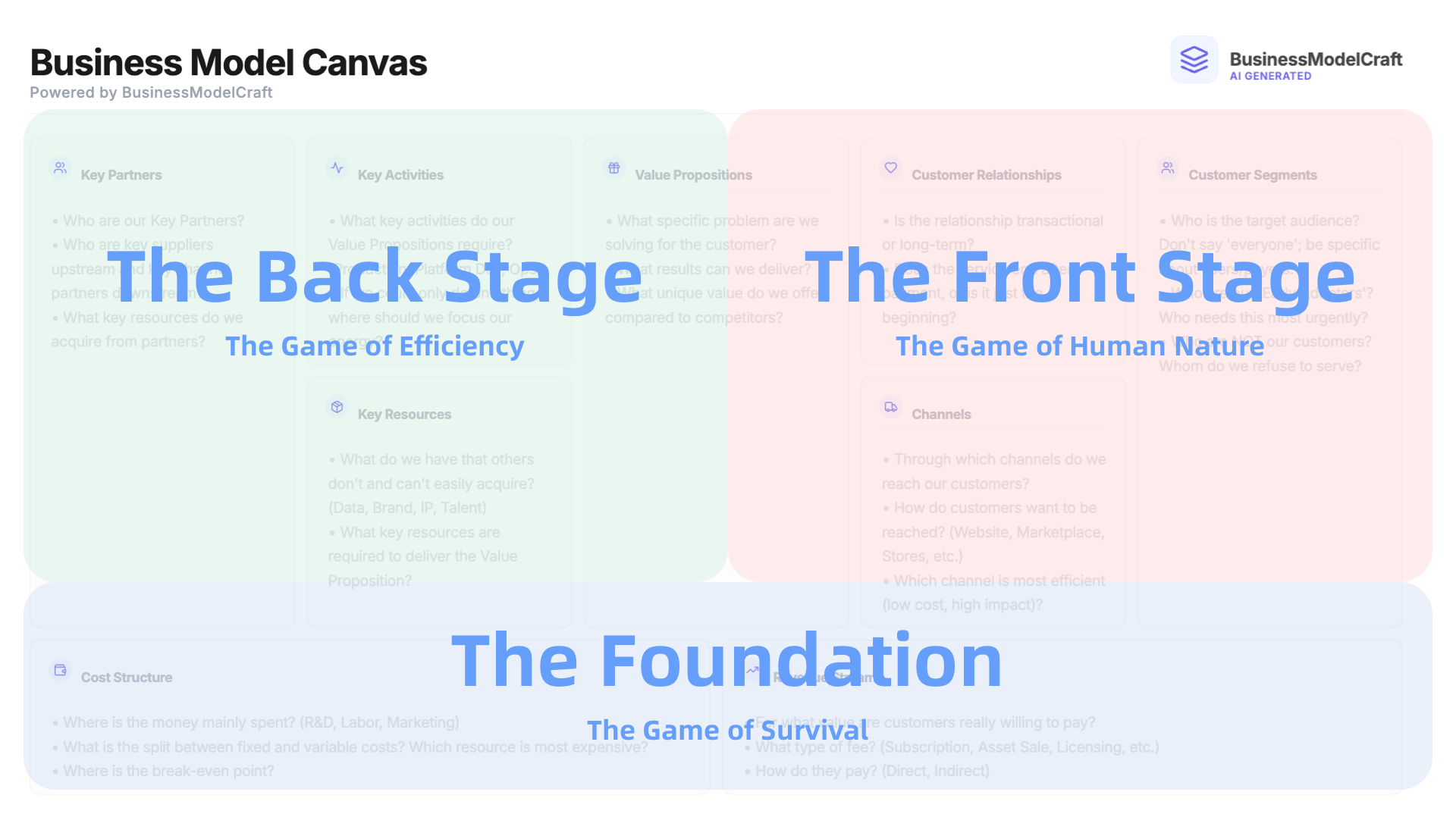

The BMC is the first step of execution. The canvas actually consists of three distinct zones that often conflict with one another:

- The Right Side (Front Stage): Customer Segments, Channels, Relationships, Value Prop (half). This is what is visible above the water. It represents "Being Needed." It tests your grasp of human nature and the era.

- The Left Side (Back Stage): Resources, Activities, Partners, Value Prop (half). This is the engine room below the water. It represents "Competency." It tests rational calculation and efficiency.

- The Bottom (Foundation): Revenue & Cost. This is the Financial Reality Check. Plans can be beautified, market feedback can be biased, but the financial statements never lie.

The Conflict:

- The Front Stage always wants more: better service, faster logistics, nicer packaging, more SKUs. This increases value but pushes up costs.

- The Back Stage always wants less: simpler craftsmanship, fewer staff, standardized processes. This lowers costs but may hurt the experience.

The Value Proposition (Center) must balance these two. It cannot be mediocre—mediocrity is the biggest error.

The Flow: During operations, the canvas is fluid, not static.

- Early Stage: Survival mode. Cost is king. You count every penny in product definition.

- Growth Stage: MVP validated. The canvas flows to the Front Stage (Expansion).

- Maturity: You occupy market share and enter a "white-knuckle war" with competitors. The canvas flows back to the Back Stage, where efficiency becomes the key to victory.

Writing this article deepened my own understanding of the canvas that has accompanied my entrepreneurial career.

I have searched the internet and while there are many articles on the Business Model Canvas, few are "deep dives" that break it down to its core. I hope this piece provides a small spark of inspiration for those of you working hard in the trenches.

One More Thing

For years, I looked for a clean, digital tool to fill out these canvases and never found one I liked. So, in early 2026, I used AI coding to build one myself: BusinessModelCraft.com.

It’s a dedicated whiteboard for the Business Model Canvas. It supports export and features a Business Model AI Agent I fine-tuned to provide strategic inspiration while you work. It’s free, requires no login, supports multiple languages, and includes case studies of famous companies.